So, Fellow Traveler, you’re in your element, somewhere on a road trip, and you come upon what might (or might not) turn out to be an interesting detour. Maybe it’s a road sign that piqued your interest; maybe something odd you caught a glimpse of out the window, or an unmarked road or path you’d always wondered about–do you make the detour, or do you let is pass, and continue along your pre-planned route?

The answer will depend on several specific things: if you’re in a hurry, or hungry; maybe the weather, time of day, etc. But it will also depend more broadly on your motivations for why you travel in the first place, including your degree of wanderlust.

The term ‘wanderlust’ originates from German, combining “wandern” (to hike, roam, or wander) and “lust” (desire or pleasure). In honor of these origins, the title, according to my computer, is the German translation of “How strong is your wanderlust?” See below for some self-assessments of your own degree of wanderlust.

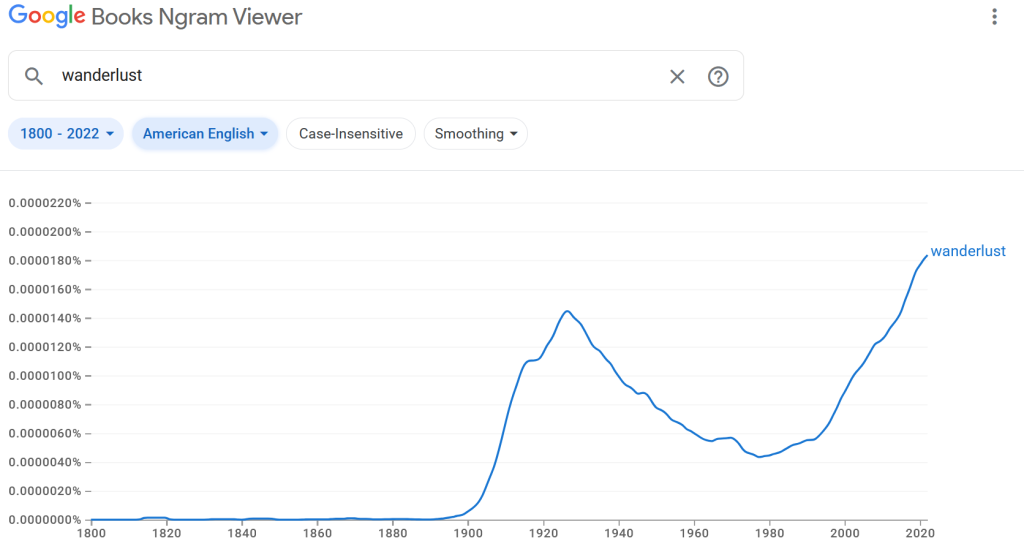

Wanderlust enters the English language in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, through translations of German literature and travel writing, and appears to now be at an all-time high level of usage, according to Google Ngram.

The American Heritage dictionary defines ‘wanderlust’ as a “very strong or irresistible impulse to travel.” Merriam Webster’s is a bit different: a “strong longing for or impulse toward wandering.”

I prefer the second, because of the word ‘wander,’ and not just ‘travel.’ Big difference. For the stories on this site, they aren’t planned in advance, but found along the way, from Dallas to Lubbock. The purpose is to wander, and to find what we find, and tell and re-tell the stories we hear.

Wandering and ‘The Wanderer’

Wandering, and the archetypal character of ‘the wanderer’ are at least as old as recorded history and literature. Odysseus, from Homer’s Odyssey, from the 8th century, BC, is perhaps archetypal wanderer, spending ten years trying to return home after the Trojan War, encountering monsters, gods, and temptations that tested his character and resolve.

Matsuo Basho (1644 – 1694), Japanese haiku master writes: “Every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.”1

John Muir (1838 – 1914), the Scottish-born American naturalist and “Father of the National Parks” was a well-known wanderer, encouraging others to do the same:2

“The tendency nowadays to wander in wildernesses is delightful to see… Wander here a whole summer, if you can. Thousands of God’s wild blessings will search you and soak you as if you were sponge, and the big days will go by uncounted.”

And from Aragon:

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

— Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (1954)

‘Travel psychology’ is a thing–who knew?

Until recently, I didn’t know that ‘travel psychology’ was a distinct research discipline, one that dates back to the 1960s. One major stream of research is focused on the reasons why people travel.

Motivations for traveling include: escape and relaxation, cultural curiosity, self-development and place attachment and belonging–that is, to forge deeper understanding and connection with places that resonate with us, or are otherwise meaningful for us.

Allocentrics and Psychocentrics

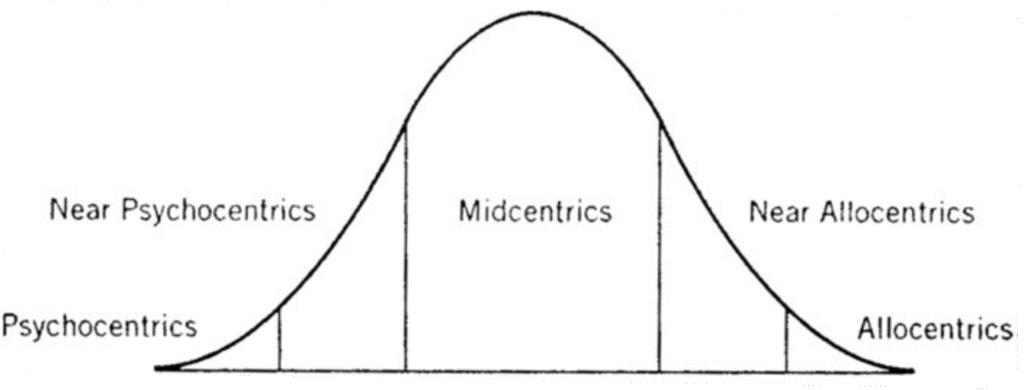

Stanley Plog,3(1930 – 2011) a pioneer in the travel psychology field, classified travelers on a spectrum from ‘allocentric’ to ‘psychocentric’ (later renamed to ‘venturers’ and ‘dependables’). Plog’s framework, originally published in 1974, is not without it’s critics, but has withstood the test of time, and is useful for our project as well.

Allocentric travelers, according to Plog, are motivated by adventure; they’re curious, open to new experiences, and more likely to engage in ‘slow travel’ which includes backpacking, road trips, and volunteer travel (‘voluntourism’).

In my own case, and certainly with this project, I’m well toward the Allocentric end of the spectrum. According to Plog, only about 2% of travelers are ‘pure allocentrics.’ I’m pretty sure my Dad was among those wonderful outliers.

If I could go back and read his thoughts (which were probably sub-conscious, although this remains up for debate between my brother and I, his travel companions), a not-very-exaggerated account might go something like this: “Wait! Here’s a small, unmarked, unpaved road, leading off the already small/unmarked/unpaved road we’re on? It’s getting dark, the weather’s unpredictable, the boys are with me, the car isn’t exactly, well, in perfect running condition, we don’t have much gas–never do; it’s 30 years before mobile phones, which wouldn’t have signal here anyway, and I don’t have hardly any cash in my wallet to pay someone to rescue or tow us out, even if we could make contact? Let’s go!” And we did. And we survived. Miss you, Dad.

As I write this, I’m reminded of just how much of that crazy behavior I inherited, pulling many of the same stunts, decades later, with my own family. Note to self: write a story about the Steamboat Springs near-disaster: “Tire chains, Officer? No, we’ll be fine”–Dad’s fault; or the ‘California gold mine shaft with mountain lion prints in the mud below and bats hanging above, but “let’s go in anyway, kids” should-have-been-a-disaster’–my fault; or of course the ever-recurring classic, performed in hot and desolate locations all across the Southwestern United States: “nah kids, we don’t need to stop and fill up before heading out across this section of desert–the food’s awful anyway (and unvoiced: ‘expensive too’)”–my fault(s).

Back to Plog’s framework, Psychocentric travelers, on the other hand, are comparatively risk averse and gravitate to more well-developed (and possibly over-developed) destinations and familiar (i.e. repeat) structured experiences.

These are the travellers who have ‘itineraries;’ who take serious those ‘last services for x miles’ road signs. They have tire chains, the good kind, onboard and properly stowed, ‘you know, just in case,’ even though they’d be unlikely in the first place to travel on roads with snow, let alone paths, on foot, with recent paw prints.

Most travelers, known as “mid-centrics,” fall somewhere toward the middle of this spectrum between allocentric and psychocentric, and, as indicated in the bell curve distribution, constitute the majority of travelers. And of course, people can make different trips, for different reasons.

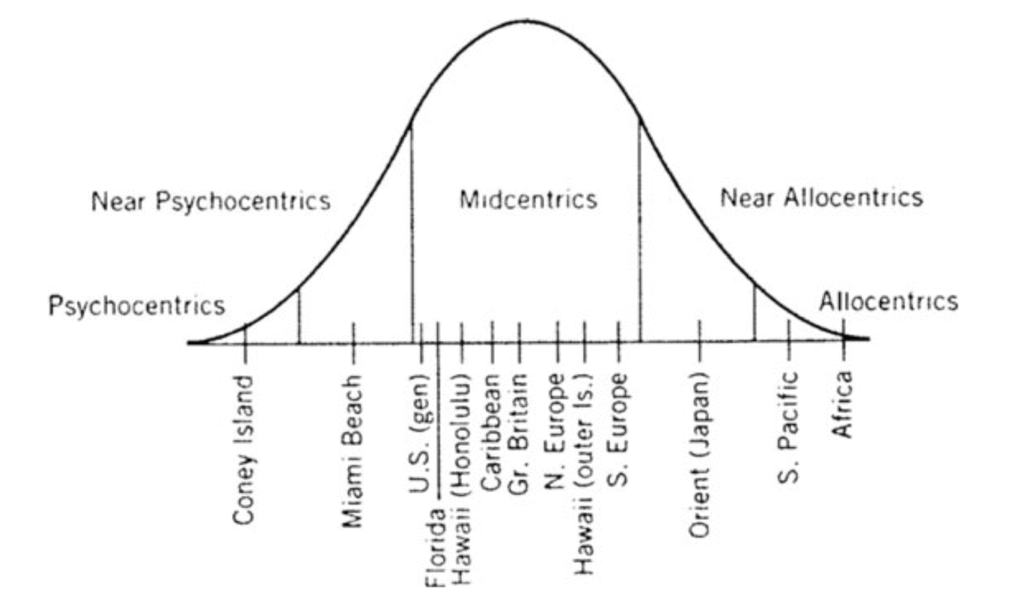

To further illustrate Plog’s model, below are a number of travel destinations, plotted along the curve according to the type of traveler that destination would likely appeal to. This data and the plots are from the 1970s, so things may have changed, but the difference between Allocentric and Psychocentric becomes immediately clear, when you consider, for example the type of travelers one might encounter on a trip to Africa, vs. a trip to Coney Island.

And of course, travelers make different trips, for different reasons, at different stages in their lives. We can envision young parents taking their young children to Coney Island (psychocentric), and that same family, later in their lives, going on a African safari (allocentric), hopefully paid for by their now-adult children, because that’s, you know, just the way it should be.

Lee and Crompton4 looked specifically at ‘novelty seeking’ as the motivation for travel. Breaking it down into four sub-dimensions–novelty for: the thrill of it, a change from routine, boredom alleviation, and surprise.

Pearce and Lee5 developed the Travel Career Ladder (TCL) framework for understanding travelers and their motivations. To understand this one, think way back to your high school or university psychology class, where you first learned about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

According to Maslow, human motivation results from the desire to get our needs met. These needs build upon one another, up through the levels of Maslow’s pyramid, beginning with physiological needs (e.g. food and shelter), then safety, then the need for love and sense of belonging, then for self esteem and finally, self-actualization.

Similarly, according to the TCL framework, your motivation to travel depends on, and corresponds with your needs, beginning with the most basic: people are motivated to travel to meet their need for rest and relaxation; then on to successfully higher-level needs and goals–strengthening relationships (e.g. traveling with friends and family); autonomy (e.g. to build confidence and self-esteem); and self-development and -actualization (e.g. travel as a way to gain new and broader perspectives on life, and/or to deepen/strengthen one’s spirituality and self-identity).

Now back to the question: How strong is your wanderlust?

Here are two simplified versions of research-backed assessments to assess your own level of wanderlust.

Travel Motivation Scale (Adapted from Pearce & Lee, 2005)

This scale adaptation, assesses broader travel motives, including wanderlust. Rate from 1 (Not Important) to 5 (Very Important):

- Exploring new cultures and histories.

- Seeking personal growth through travel.

- Experiencing adventure and excitement.

- Connecting with new people and places.

Scoring: Scores range from 4 to 20. High scores (16-20) reflect deep wanderlust and a quest for meaning, while average scores (10-14) are typical for casual travelers.

My score here: 19. So 5/5 in all but one aspect–adventure and excitement. These days, my travel and wanderings, cherished though they are, are motivated more by personal enrichment, rather than ‘excitement.’ Although, the rattlesnake i almost stepped on while traipsing through an overgrown cemetery outside Seymour, while search for a civil war veteran’s grave–that was certainly a kind of ‘excitement,’ albeit of the unintended kind.

Novelty-Seeking Scale (Adapted from Lee & Crompton, 1992)

This scale measures your desire for new and exciting travel experiences. Rate each statement from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), then sum your scores:

- I want to experience new and different things when I travel.

- I enjoy the thrill of being in unfamiliar places.

- I seek unique destinations off the beaten path.

- I prefer spontaneous travel over planned itineraries.

Scoring: Total scores range from 4 to 20. Higher scores (16-20) indicate strong wanderlust, like an allocentric traveler (adventurous, like Aragorn). Average scores in studies (about 12-14) suggest moderate curiosity, common in the general population.

My score here: again 19. So 5/5 in all but one–the thrill of being in unfamiliar places. Alas, age takes its toll, and I am a bit more cautious these days, compared to my younger risk-taking self.

We each have our own unique motivations for ‘hitting the road’ or getting away. Hopefully these frameworks can help you better understand and articulate your own, and get more from your next travels and wanderings.

Gute Wanderung!

- The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches. Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa, Penguin, 1966. ↩︎

- Muir, John. Our national parks. Houghton Mifflin, 1909. ↩︎

- Plog, Stanley C. “Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity.” Cornell hotel and restaurant administration quarterly 14.4 (1974): 55-58. ↩︎

- Lee, Tae-Hee, and John Crompton. “Measuring novelty seeking in tourism.” Annals of tourism research 19.4 (1992): 732-751. ↩︎

- Pearce, Philip L., and Uk-Il Lee. “Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation.” Journal of travel research 43.3 (2005): 226-237. ↩︎