Below are two stories, both with the purpose of explaining this project. One of them I wrote in the Spring of 2021, as I was just beginning; the second one’s from the Summer of 2025.

Ridiculous perhaps, but it took me that long, about four years, working off and on, to really understand what this project is. I know now. It’s a deep map of the journey from Dallas to Lubbock. In the second story, I explain what I mean by ‘deep map.’

Rather than discarding the first, I include them both here. Hopefully the content, and also the very slow coming to awareness of what this project is all about, are interesting for you, Fellow Travelers. Bon Voyage.

Spring, 2021

The ideas, thoughts and unanswered questions that have eventually led to this project have been with me for a long time, years in fact. Questions about the people and places on the way from Dallas to Lubbock, what it’s like to live here, what the stories are. These questions float up into my thoughts during this, or any long road trip really, that takes me out of the city and far into the countryside.

So after years of wondering, I’ve finally decided to do something about it. I started this project to find some answers, and created this web site to share what I find.

Nothing more complicated than that, really. Please join me.

For those who’ve spent time in the Western or Southwestern US, a drive of five or six hours, even more, is not that big of a deal. Some of us look forward to these trips. The long and lonely stretches give your mind a chance to wander, to really think things through. And the occasional small town or gas station, they seem to appear on the horizon just in time to keep you from overthinking those very same things.

I stop to fill up. I go inside, get a cup of coffee. Weak, of course, but hot at least. I say “Hello” to the person at the register.

‘Where do they go when they finish their shift?’ I wonder. ‘To their homes, stupid,’ continuing the conversation with myself. But what’s it like, to not just pass through, but to live here? What do they do for fun around here? Any nicknames for the locals, or for those in the next town over? Any rivalries? Is there a town gossip? Of course there is, but do they stir up trouble?

In my younger years, I too lived in a small town, so I have some idea. But it wasn’t this small town; maybe it’s different here. Still, it’s best not to pry. Better stick to ‘normal’ questions.

“Next time I’m through here, where’s the best place to eat? Is that barbecue place any good? It’s alright? Okay. Thanks, see you later” I say to the clerk, knowing I probably never will.

I head back to my car as someone else, from somewhere else, is pulling in. I wonder where they’re going. Maybe they wonder that about me as well. Or not. Either way, you’ll never, ever, know. Because soon you’ll both be on your way, each at 75 miles an hour, in opposite directions, while the clerk remains, tending the register, sweeping the floor, turning out the lights, locking up…

So one reason for this project, a selfish one perhaps, is that I’m tired of not knowing anything about these places. It doesn’t sit well with me, that an hour from now, I might not remember much at all about this place, other than next time through, I should stop somewhere else for coffee.

I’m just getting started with this project, but I’m optimistic. I’m struck by the variety and the richness of the stories I’ve heard already, and motivated by those still to be found along this 330 mile route.

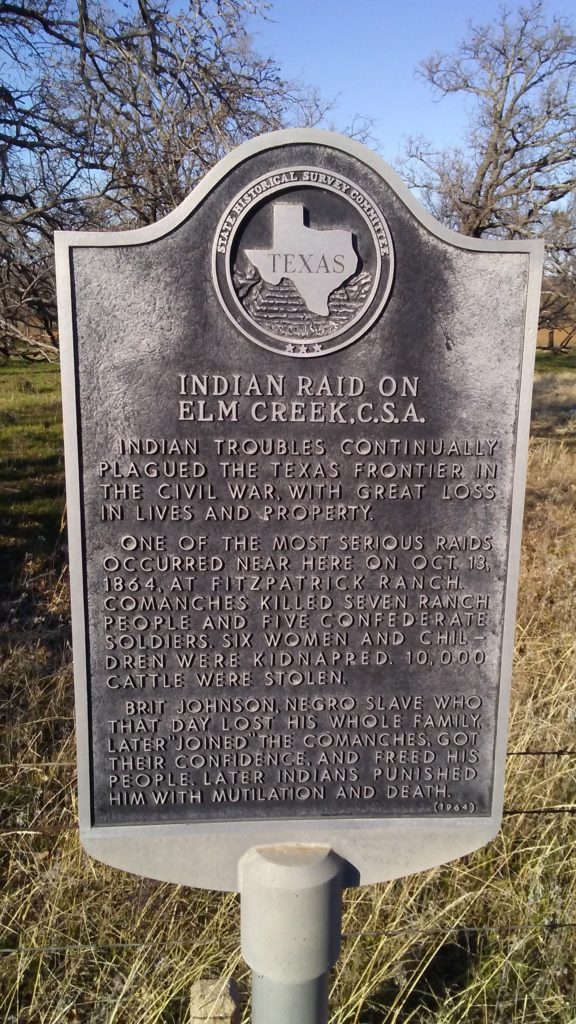

It’s a near-infinite number I’m sure, with current stories layered atop historical ones, and whatever envisioned future ones you might layer atop those–like a kind of three dimensional map, with past, present and future. A single roadside marker, for example, once you look into it, opens up 150 years of interconnected stories:

Today I’m headed west on Highway 380, near Newcastle. Beautiful sunny Saturday afternoon, low 70s–uncharacteristically warm for late January, cattle grazing on both sides of the highway.

But if you’d been traveling through here in the autumn of 1864–on October 13th, to be exact–you’d have come across a very different scene, a tragically violent scene where 12 people died, six were kidnapped, and thousands of cattle stolen during the Indian Raid on Elm Creek.

Excavation at this site might turn up some buried shell casings or other artifacts. But I for one don’t need any physical ‘proof’ to already feel the realities of this place, both past and present.

The story extends effortlessly in any number of directions. We could, for example, explore the life of Millie Durgin, one of those kidnapped during the raid, an infant at the time, who went on to live a long life with the Kiowa who abducted her, bearing nine children, and with 32 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren.

Or we can bring the story 100 years closer to the present, by exploring the Young County Survey Committee, the group responsible for erecting this marker in 1964, a century after the incident occurred. Committee members included: Mrs. J. W. Bullock, Committee Chair, of Newcastle, Texas, Mr. George Terrell and Dr. Kenneth Franklin Neighbors, a historian, who wrote several books on 1850s American Indian relations. He taught at SMU in Dallas for several years, and took a balanced approach to his scholarship, that neither romanticized nor vilified either side.

Dr. Neighbours was also, say those who knew him, a flamboyant character and life-long bachelor. A voracious reader, he’d fill one room with books, then move on to the next, in the sprawling Victorian house in Wichita Falls where he lived in later years. The librarians in charge of archiving his collected works and papers told me they had their hands full, and with a lot of work still to do. His life’s work and still-felt presence add yet another layer to the history of this place along Highway 380.

As for it’s future, I’ll hold off on that, until I learn more. What I can do now, is imagine a kind of radio that would allow us to tune in, not just to different broadcast frequencies, but to different times and epochs. Traveling through this place, we could tune in to the ‘news’ of today, or turn the dial back to hear the sounds of the construction crew as they installed this marker. Or farther back still, to hear the screams and gunfire that once erupted on this very spot. And how far into the future would we have to tune, to hear languages other than our own, or sounds altogether unintelligible?

Update for 2025: A Deep Map of the Journey from Dallas to Lubbock

Today is Monday August 4th, 2025, and it’s time for an update.

Because as ridiculous as this might sound, after working on this project off and and for four years, I’m only now beginning to finally understand what it is: It’s a deep map. More specifically: This project is a deep map of the journey from Dallas to Lubbock.

What I know now, but didn’t know then, is that the ‘three dimensional map’ described above is very similar to what author William Least Heat Moon calls a ‘deep map.’ He coined the term, and demonstrated it, masterfully, with his 1991 book “PrairieErth,” a deep map of Chase County, Kansas.1

A deep map, according to Moon, might include an actual, physical map of a place. But it goes far beyond that, and might also include: folk lore, geology, natural history, and local stories, etc, all interwoven to create a richer, fuller and more immersive account. This in turn can you better connect with a place, or literally with the earth.

Moon chose the location in Chase County, specifically the area around Cottonwood Falls and the Flint Hills region, because it’s right in the heart of one of the last remaining tallgrass prairie ecosystems in North America, the preservation of which he considers vital. He also chose the location because it seemed empty to those who didn’t know it well. Says Moon: “I wanted to try to write a book about a place that Americans thought there’s nothing that happens there of interest,” but was actually a place rich with stories, past and present.

As I hope you can see, Moon’s work aligns very closely with what I’m trying to do with this project, even though I didn’t understand it, and couldn’t yet articulate it, when I began. I started out with the simple idea to collect some stories of the people and places along the way from Dallas to Lubbock. And that remains the central focus, it’s just that the scope and the depth of the stories I’ve come to be interested in, have increased.

The discovery of Moon’s work was something of a ‘Eureka!’ moment for me. Standing on the shoulders of giants, indeed. It proved a ‘three dimensional map’ wasn’t as crazy as I sometimes thought, especially when others reacted with: “OK, now tell me again, what is it exactly that you’re tryin’ to do’? A deep what?”

For me at least, the project is clear now, and on a firm footing: I’m creating a deep map for the journey from Dallas to Lubbock.

Dear Readers Fellow Travelers

Before going any further, I want to explain to you why I’m providing an ‘update’ rather than just getting on with it.

I see this project as an exploratory journey, itself a kind of ‘road trip.’ Because it’s exploratory, there will be some doubling back, some detours, maybe even a few dead ends.

But rather than going back later to revise everything, I’m leaving it as is. I’m leaving the outtakes in, so to speak, because it’s all part of the journey. And so that you don’t get lost during any of these detours, I think it’s better if you come along for the ride. So from here on, I’ll think of you as Fellow Travelers, if that’s ok with Y’all. I’ll scooch over. Hop in.

Three important adjustments to our deep map

There are three places where this project heads off in a slightly different direction than Moon’s.

First, I don’t want these to be ‘my stories.’ As much as possible, I want them to remain the stories of those who shared them. I try to keep a light hand editorially when sharing others’ stories, and make use of audio recordings, so we can hear their stories, in their own words. Eventually, although it’s a big step up in complexity, I hope to include video as well. There’s some down side to video, though, because it leaves less to your imagination.

Second, I want to include not only the past and present, but also the future. Past and present do make for great stories; they’re good, low-hanging fruit, But there’s simply more to harvest here. This is why the inclusion of geography and the underlying geology are so important–they’re two of the most powerful and visible ways, for tying the past and the future tightly together.

Because changes in the natural environment are slow (in human scale), we tend to underestimate their power. We write or talk about how geology or geography ‘influence’ our lives today, when in fact they largely ‘determine‘ how and where we live them, both now and into the future. If the super-continent of Pangea hadn’t broken up into pieces, the arid lands that today we call Texas might still be an ocean floor, just as it was long ago. These tectonic forces never cease, of course, creating our future, every single day. This calls for some creative effort to envision what might become.

Third, with this deep map, I’m looking not only at the people and places, but also at the journey that connects them all; the transitions that unfold as we travel through the changing geography.

What’s the benefit of a deep map?

So deep maps go beyond 2- or even 3-dimensional maps, but their real power comes not from the number of dimensions, but from their ability to evoke meaning and emotion through stories, told with text, images, or even sound and music, all working together to connect or re-connect you to places or journeys that are important to you.

If the author is successful, a deep map should resonate strongly and meaningfully with those familiar with the place or the journey through it. And it should enable those who’ve never traveled there to know the place, even ‘experience’ it a little, to get a feel for it, through text, image, and voice.

At some point in your life, you’ve probably been told that it’s not only the destination that matters, it’s the journey. “Don’t forget to stop and smell the roses along the way” people tell you. That’s pretty good advice, and you can think of a deep map as a kind of method for doing precisely that; a method for capturing more of whatever it is that makes a journey memorable and meaningful for you.

Enough with description, let’s offer an example.

Imagine it’s mid-summer. You’re planning a trip with your wife, to get out of the heat and up into the cool of the mountain air for a couple days. It’s a destination you know well, but haven’t been to in years, not since you used to take the family there, when the kids were young.

You pull up Google Maps on your phone, but some of the landmarks and back roads, more like trails really, don’t appear. But not to worry. You go into the back bedroom, empty now except for an old dresser–the ‘chest of junk drawers’–as your wife calls it. You have to rummage around for bit, but you find it: the old paper map you used for years, long before maps were things we read from screens.

It smells musty as you unfold it onto the kitchen table. The markings along the folds are gone, but the detail and the back roads are all there. That first turn, off the main road, the one that’s easy to miss, especially in the summer when the foliage is thick; the little ‘crossed pick and shovel’ icon, marking the abandoned mine shaft you didn’t explore, because of the abandoned mine shaft up the road that you did explore, on an earlier trip, with family in tow and disastrous consequences, narrowly avoided.

Right at your planned destination there’s a small hole where you once stuck a pin, with an exaggerated flourish, to show the kids precisely! where you all were headed. A part of the route is drawn with pen, because your daughter had traced the road with one of her colored pencils, and you got upset and told her she shouldn’t mark up the map like that. You tried to erase it, but the print came off too. Then she cried, then you cried too, and you hugged her tight, saying you were sorry and that it was just a stupid map after all. You had her draw it back in, for good this time, with a pen. And now, decades later, another tear wells up, but with a smile this time, adding another layer of meaning to this old map.

Except, it’s not just an old map, it’s a deep map, deep with memories and meaning, and hope and anticipation for the future.

I’ll offer one last example of a deep map, taken from a portion of the trip from Dallas to Lubbock where you arrive into Jacksboro. I’ll offer a couple versions: what I saw when I first began making this trip a few years ago, and then a deep map version, of what I see and feel when I travel through there these days.

From the very first trip I made from Dallas to Lubbock, I’ve always enjoyed arriving into Jacksboro. Along SH 199, Jacksboro Highway, there’s a slight climb on the way in, which is nice, coming from the flat lands of Dallas. The scenery has changed–and because you’ve escaped the urban crush, that change in the scenery is actually visible. Arriving into Jacksboro feels like you really are getting out of town; that the trip has finally begun. At about 90 minutes into the journey, it’s also a good time to stop for a stretch.

So that’s why I’ve always enjoyed the arrival into Jacksboro, and still do–nothing about that has changed. What has changed, is the depth of understanding I now have about this place; how the natural environment, the history, even modern industry (and a really good burger joint–lest we take ourselves too seriously) are all intertwined.

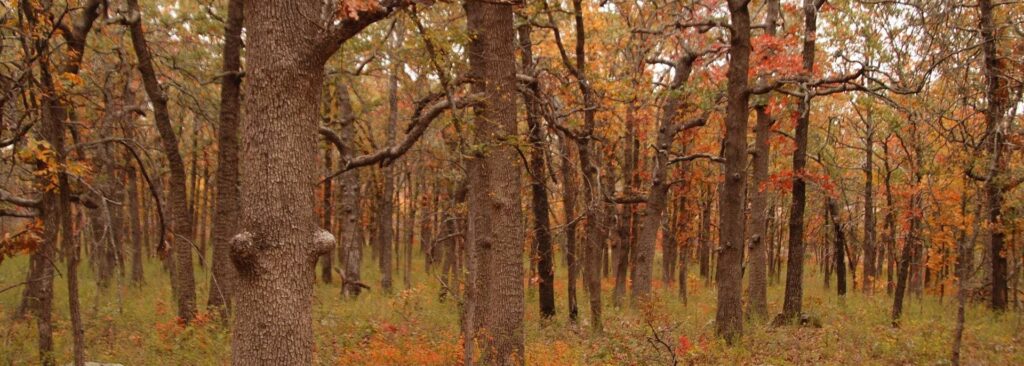

Now when I arrive into Jacksboro, I know that much of the ‘change in scenery’ is because I’ve entered into the Western Cross Timbers, a region of old-growth forest, of primarily post oak and blackjack oak, that begins in Fort Worth and stretches northward through Jacksboro and into Oklahoma and Kansas.

In the deep, rich, clay soils of Dallas, these same species of oak grow straighter, taller and faster. But here, growing conditions are harsh, there’s less rain, more wind, and the soil is sandy and thin atop the underlying limestone. Out here, these trees have learned to hedge their bets, sending up multiple shoots from a single tree–if one trunk fails, others carry on.2 The result is dense clusters of trees, with trunks and limbs gnarled and twisted, and rarely topping 30 feet in height.

If these old trees could talk to us, what stories they could tell!

But there’s one more characteristic of these trees that makes them of particular interest for this project: their age. The Cross Timbers, including the Western Cross Timers where Jacksboro is located, is often referred to as the Ancient Cross Timbers (note the photo credits above), with trees ranging from 200 to 400+ years old. In other words, not only are these forests a striking change from what you see in Dallas, they’re also a direct and still-living link to the history of Jacksboro and the surrounding territory.

In this project, I often write about historical events. But sometimes, that history is simply too long ago for us to easily understand. We know that supercontinent Pangea, mentioned above, broke apart to form several continents, including North America–easy to understand. But when you hear this happened 200 million years ago, unless you’re a geologist, can you really make sense of that? The limestone outcroppings around Jacksboro are even older, at 300 million years. What geologists call ‘deep time’ is difficult for us to get a handle on.

But these old oaks that surround Jacksboro give us a unique opportunity. Without question, they’re ancient–many older than our country–but not so ancient that our eyes glaze over. And the opportunity is this: at 200-400 years, that means they’ve been around, and particularly for the oldest ones, for most of the recorded history of Jacksboro and the surrounding territory. Not only were they alive through that history, but they played a much more active role than many know–including me until say, 6 months ago.

Before settlers came along, Native Americans used the timbers as a natural barrier, for herding buffalo during hunts.

When the settlers did come along, in the 1800s, the dense growth over rocky terrain of the Cross Timbers were obviously a major impediment to their western travel, earning them the nickname “Cast Iron Forest.”

Explorer and writer Washington Irving famously wrote:

“I shall not forget the mortal toil, and the vexations of flesh and spirit, that we underwent occasionally, in our wandering through the Cross Timbers. It was like struggling through forests of cast iron.” Washington Irving, A Tour on the Prairies, 1832

Later, peaking in perhaps the 1850s, when these two groups eventually came together, they clashed. For the Kiowa and Comanche and other tribes, the Timbers, with its dense growth and tangled understory became a hidden place from which to launch and attack

“The underwood is so matted in many places with grapevines, green-briars, etc., as to form almost impenetrable ‘roughs,’ which serve as hiding-places for wild beasts, as well as wild Indians; and would, in savage warfare, prove almost as formidable as the hammocks of Florida.” Josia Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies, 1844

As it turns out, the forests and underbrush also turned out to be a hiding place for the Settlers, from just such such an attack by the Indians, according to this account of the Elm Creek Raid described above, where “Mr. [Peter] Harmonson and his boys escaped [from the raid] to the cross timbers, which was a short distance away, and obtained their safety.”

Jacksboro was at the leading edge of these clashes, and was the site of first-ever trial of American Indians in a US court, when three Kiowa chiefs–Satanta (White Bear), Satank (Sitting Bear), and Big Tree (Addoeette)–were arrested for the infamous Warren Wagon Train Raid, which occurred about 20 miles southwest of Jacksboro in 1871.

Seven teamsters were killed. One of the survivors somehow managed to make it the US Cavalry garrisoned Forth Richardson, which you can still visit today, about 1.5 miles south of Jacksboro. The other survivors, it is believed, took refuge in the Cross Timbers, near Cox Mountain

The oaks of the Western Cross Timbers have played an active role in the history of Jacksboro, but they never have and they never will play favorites.

So to close this out, one could argue that the above is not really a deep map, it’s more like a kind of textbook on a bit of the topography and the related history of Jacksboro. That’s not wrong, but that’s what’s involved in creating a deep map. And creating a deep map is a lot of work. Like most things of value, they required investment of time, effort and dedication.

In the example above, of Jacksboro it takes a lot of research. In the earlier example of the family camping trip deep map, that deep map too, was a lifetime in the making. But the payoff comes, when you travel through.

With this background in place, having done my homework to create this deep map, I can tell you that I arrive into Jacksboro, I pass Fort Richardson on my left, and think about there history that unfolded right there, about Thomas Brazeale, one of the survivors of the Warren Wagon Train raid, notified General Tecumsah Sherman who had just made it to Fort Richardson, having traveled through the exact same spot just an hour before the attack.

On my right is an old red oilfield boom truck. Big, beautiful, bright red. Probably from the 1960s–the epitome of tough. Oil and gas are foundational to the modern economy of Jacksboro. And oil and gas are here, because limestone is here, since 200 million years ago, with its cracks and fissures two miles below, where the oil and gas collect. And two miles above that, it’s the cracks and fissures of limestone at the surface, that allows for just enough soil to allow for the post oak and black oak trees to take root and grow.

Up the road, at the first of just two traffic lights, is Roma Pizza, a good place to get some pasta or pizza, a place where you should park around the back, and come in through the back door, you know, like the locals do. Past the light the twon square and the impressive Jack County courthouse are to your right–the fourth built there, the second one being where the Indian trial was held. Out front, note the honoring the state champion football team–an impressive feat in Texas, for sure.

Across from the courthouse is a building from 1909, one of the first, and now oldest buildings in the entire county. Atop that building, is a stone with 1909, but the last “9” is carved upside down, like an odd-shaped “6.” Intentional? A stone mason’s mistake? I don’t know, but I do know it’s another story for another time; one I will pursue, trust and believe.

Downstairs is JB’s Steakhoue and B&B. Upstairs, there are fully-restored period-correct hotel rooms, with giant cast iron clawfoot tubs where you can have a soak, if you happen to arrive in the evening. In the morning, having slept like a boss, grab a Starbucks on the first floor, or if you’ve slept in, and you’re ready for an early lunch, drive down the road a block to get a burger at Herd’s, one of the best anywhere, a place that’s been serving them for 75 years. Ancient rocks, ancient trees, ancient burger joint–all ancient and still going strong: what’s not to love about Jacksboro, seriously?

While in town, you can check out the Jack County Museum, and learn that Jacksboro was where the 4-H club really got started (not Ohio. Sorry, Ohio), check out the local Library and say hello to Lanora Joslin, the first person I was honored to share their story on this site. She can also tell you about her Father’s experience in WWII, one of the 63 Jackboro Boys, of the 131st Field Artillery unit, part of the “Lost Battalion” and their harrowing POW experience building the Burma Railway and that inspired the “Bridge over the River Kwai.”

And finally, on your way our of town, past the high school, newly rebuilt after the EF3 tornado that came through in 2022–no major injuries–you take a big sweeping left turn, onto Highway 114. On either side will be some of your best, close-up views of the Cross Timbers. While the settlers through here were lucky to make three miles a day, you can fly through at 75 miles an our, in air-conditioned comfort, and with the knowledge of at least a few of the stories that these old trees have to tell.

So these are two examples of deep maps, with the second taken from the route from Dallas to Lubbock. And although editors will tell you to be careful to not inflate the expectations of your readers–in this case fellow travelers, I will tell you that this is just one of the segments of the journey, and that the entire route is filled with successive sections of an overall deep map that are every bit as ‘eventful’ as is this one above.

And remember, the time scales we’re talking about here are staggering: Mrs. Erosion is a master sculptor, but she works slowly, taking 30-50 million years, along with colleagues Mr. Tectonics and Mr. Ice Age to sculpt the roughly 600 foot climb between Jacksboro and Dallas. Mrs. Erosion will make at least two more appearances during our trip, and in more dramatic fashion, beginning about 30 miles along down the highway, with our slight descent into the Permian Red Beds.

Sonow, for me, Jacksboro is the two founded it 19xx, an area of old growth forest that was a significant fact in the wetward settlement and violet/deadly classeh. This is what it is for me to drive through here. And finally, it’s also a place where I can get a great burger, at Herd’s where they ‘ve bee n serving great burgers, for x years. A great cheeseburger has a perfectly rightful place in a deep map.

And, as we will see elsewhere, the entire trip, from D to L, is a succession of these scense, transitioning from one to the other.

So with a project like this one, is it possible to create a deep map of a much larger area–specifically, the 330-mile journey from Dallas to Lubbock? I don’t know about the level of ‘resonance’ I as an author could muster, among you the readers, but do believe it’s possible

With the benefit of hindsight, it would be folly to try and describe the journey between these two cities, without considering the 100th meridian, and the impacts it continues to have on our daily lives.

Deep maps: You’re already making use of them, and if not you should be

And finally, I want to say that the idea of a deep map need not be some intangible theoretical construct, but rather, it’s something that you’re likely already making use of, or could be, for the enrichment of all your travels, long or short.–as you can see from tje JB example

Think of, for example, any path or journey you’ve taken repeatedly, one you know well, and one that is/was for whatever reason, important for you. It might be the path you took to school as a child, or the commute you now take to work.

As a child you knew what friends (or enemies) lived along that way; where the nice and not nice dogs lived. As a commuter you know every turn; where to stop for coffee, and where not; you know to be careful at that one intersection where kids await the bus in the mornings, or that feeling of ‘decompression’ in the evening, when you make the last turn, finally onto your own quiet home street. Now just imagine projecting all that you know and feel about that well-known path, onto a kind map of the journey–that’s a deep map.

‘How to’–focus it on the unitary experience, and make it unique. And it can also be unique to you.Perhaps you’d prefer the italian–dont let that heavy curtain fool you–they’re open. Park ’round back and swagger in like a local, or the mexican place on the square, another good option. Or maybe for you, it’s not the food at all, or not even Jacksboro, maybe it’s later, when it gives way to the prairie.

I met with a guy from Parks and Wildlife. His deep map is bugs, nuttin but bugs, and he can talk at leangth about the bugs

You are the tour guide. What do you show your guests? To where will you direct thair attention?

Psychocentric vs. Allocentric

Coney Island vs. Safari.<==start with these. Imagine first 2 trips–one to coney island, and one to the savannah

This one is way toward Allocentric. This site might be kryptonite for the psychocentric traveller–what in the actual hell is wrong with that guy–he doesn’t even give stars or rating or speicic driving directions–what’s the point?

Maybe they’re right. Or rather, I want to say, I undertstand these sommecnts. And we all travel at different times for different reasons.

Still I certainly dont want this to be anoying for them, or anybody. So what I will try to do is this: Stureutre it so that there is a main route, from D to L. A farily brief discription of the route. And you should be able to cruise through that pretty quickly. And the more psychographic you are, the more this may appeal.

And then, I will go deeper, detaours, etc, off the main route. And yu can spend (waste) as much time as you want, on the backroads, and diving into the minutae, but always with a hyperlink to get you righ back onto the main road.

This can be your concierge, your travel guide, from D to L, and one which can accommodate or quicker or slower pace of travel.

Conceptually, I think the structuring idea makes sense. Can I pull it off? Not sure. But I will try. And you can watch the exploration unfold.

- Moon’s “Blue Highways,” the books of the great John McPhee, and William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County, if there are any fans of classic American literature out there–they all made use of deep maps, even though they may not use the term explicitly. ↩︎

- The sending up of shoots is referred to as “vegetative propagation” as opposed to “seed reproduction.” ↩︎